The Overly Involved Guide to Cooking

Making the most of food in your games of Dungeons and Dragons

Why does food matter?

Your party is crowded around a small rickety table in the first tavern they see upon entering a new town. You extensively describe the sight of the denizens of that new city, emphasizing just how new and interesting this location you handcrafted is. The outfits of the citizens, the thugs lurking in the background, the workers grabbing a pint after a long day at the docks, maybe the armaments of a particularly interesting mercenary. Perhaps you even describe the smells that pervade this greasy establishment. But what are they eating? Gruel? Mutton and vegetables? A pint of ale? What food is here that they haven’t eaten before at every other tavern they’ve experienced on their travels. Why does this coastal city have the same cuisine as the one they visited in the desert mountains, or the great plains, or the frontier town near the haunted swamp?

Food is such a large part of the human experience, and particularly the experience of exploring new and exotic places. That excited feeling you get when having a new dish in a new city, the first memory of a cuisine you would fall in love with, the nostalgia of a dish you haven’t had in years that still tickles your taste buds. Even more than our own individual experience of it, it's the culmination of every person in a specific area’s experience with it. It's a reflection of the culture of an area. How a group of people approaches the idea of food and eating can be just as important as what they’re eating. Finally, it's a representation of the economic and geographic factors that define an area. What ingredients are native to the area? What crops or animals thrive in those conditions? What other cultures is that area trading with to receive ingredients outside the boundaries of their own fields? A common spice in one nation may be a delicacy far away, or maybe an ingredient isn’t exported at all, whether by local importance or infeasibility of transport.

What we eat is a huge part of who we are, who we’ve been, and what we experience as we encounter the new. I would argue that those three questions are the core part of any role playing game such as Dungeons and Dragons. As Dungeon Masters our primary challenges are in giving our party vivid and believable answers to those three questions every time they learn more about the worlds we weave. For that reason, food is a massive part of the campaigns I run, and I have created this overly extensive resource to offer some of the ideas and systems I’ve created to incorporate it into your own worlds. All of these are compartmentalized ideas, take them a la carte, feel free to modify them, and as always, balance them according to your own campaigns. But without further ado, let’s jump in.

Cooking

This is the process of creating a dish that is greater than the sum of its parts, or at least doing our best job at it. We’ve all been there where we leave something on the stove too long, or add a bit too much salt, or not enough salt, or should have cut up our ingredients thinner, or thicker, or more even, etc. The list goes on and on, with so many moving parts a lot can go wrong. Preparing, combining, heating, and plating ingredients takes a certain level of skill and experience.

Mechanically, Cooking is a new skill to add to the likes of medicine and survival. The stat that it relies on is Wisdom, however I often allow my players to use another stat to accompany it such as Intelligence for the knowledge of how to use available ingredients, or Dexterity for the performance of fine motor tasks. Whatever skill a player decides to take it under, is the skill that it will be based on. Make sure that this flavors how they approach cooking as well. An Intelligence based cook may be constantly doing gastronomical experiments, while a Dexterity based cook may flaunt their work based on its precision, and so forth.

When it comes to the skill check, at its core, all you need is ingredients and time. If those two requirements are met, the player rolls a cooking skill check to see the quality of the outcome.

That’s a perfectly good ruleset for incorporating cooking as an action your players can take, go forth and implement the cooking skill into your games!

…But this guide is overly involved for a reason. Let’s go through all of the nitty gritty details that can affect a dish.

Ingredients

You can’t cook a dish without something to start with, but aside from the material component require to casting “Make Tasty Sandwich”, do the ingredients have any effect on the final dish? I would argue they definitely do. Go ahead and make 2 grilled cheese, one with fresh dairy made cheddar, and the other with a few month old block of gruyere you found stuffed behind the fridge. I’m pretty sure there will a difference. The other part is a mechanical challenge. How do we calculate just how much help these ingredients give a struggling chef? I have split up ingredients into having two factors, Type and Quality.

Ingredient Types

In DND all things must be measured and managed, and for the sake of mechanical simplicity, there are two types of ingredients: base ingredients and modifier ingredients. Base ingredients can be grouped into meats, fruits and vegetables, and grains. A simple way of thinking about it is that your base ingredients give the backbone of the dish. They are the parts that are necessary for the dish to exist in its intended form. Pretty hard to make a taco without a tortilla and some fillings. You could substitute out the tortilla with bread, and that carne asada for ham and cheese, but would you still call that a taco? Probably not because you are lacking the base ingredients.

Next we have modifier ingredients such as herbs and spices. These can brighten up the dish, or give it a specific personality. Two sets of base ingredients can be completely different dishes with different modifier ingredients. Think about chicken noodle soup. Chicken, broth and noodles. Whether you add lime, cilantro, and lemongrass or thyme, parsley and oregano can determine whether you’re eating in Asia or Europe. But it is undeniably chicken soup regardless of the added spices and herbs. That’s because those are modifier ingredients.

Ingredient Qualities

A tomato can be at the peak of freshness or a soggy mess, and that fact will show in the final dish. While you can still make edible food with less than stellar ingredients, starting from a good foundation always helps. That isn’t to say you can’t burn the perfect steak however. The roll of the dice is what keeps D&D interesting. The best laid plans of mice and men and all that.

Disclaimer: In a lot of my rules, things are done with modifiers. I know that 5e has largely tried to move away from the complicated arithmetic of 4th Edition, and while I agree that it cluttered up combat, I do stand by a modifier system when it doesn’t need to be recalculated every single round. A perfect example of that is skill checks. But feel free to ditch a lot of these modifiers for advantage if you want to be more pure to the spirit of 5e.

Ingredient Qualities are separated into tiers as follows.

Tier 0: -3 modifier

You really shouldn’t be eating this unless you’re desperate.

Tier 1: +0 modifier

Its a basic edible form of that ingredient

Tier 2: +1 modifier

While far from outstanding, something sets this ingredient apart from others

Tier 3: +2 modifier

This is prime from the source and will spruce up any dish

Tier 4: +3 modifier

People pay top dollar for this level of quality

Tier 5: +4 modifier

Most individuals will never work with an ingredient this exquisite in their life

This tier system allows for a lot of variety in the ingredients your players can source, the purveyors they source them from, and maybe even specific tasks or quests that they need to undertake to secure the best of the best.

As far as bonuses go in the skill check, you may add the bonus from one modifier ingredient and one base ingredient. The modifier you add is the lowest tier of the ingredients included of that type, whether base or modifier.

For example, if you use a Tier 2 Grain, a Tier 3 Meat, a Tier 4 Spice, and a Tier 1 Herb, you can add the bonus for a Tier 2 Base ingredient (the grain) and a Tier 1 Modifier Ingredient (the herb).

Total Ingredient Bonus = Lowest Tier Base Ingredient Bonus + Lowest Tier Modifier Ingredient Bonus

You might look at that and think, wait, my players are going to get up to a +8 on checks just because they found some nice groceries? To that I say, if they go on a quest that is difficult enough to procure legendary ingredients, then let them! It will make a great story. Either they utilized the amazing ingredients to their full potential, elevating it to new heights that most mortals will never consume. Or on the other hand, they get to be remembered as the guy who burnt the golden Roc’s eggs. On average, they should be dealing with Tier 1, 2, and 3 ingredients. Tier 1 are pretty standard in most markets. Tier 2 require a discerning eye and some more coin. Tier 3 generally require a special purveyor or a trained hand harvesting it straight from the source. Keep those things in mind when assigning, and working with, ingredient tiers.

Salt

Anyone who has a basic knowledge of cooking knows the importance of salt. It is necessary in almost every dish in some form, whether we sprinkle on the white crystals we take for granted, or we integrate some salty component like soy sauce or cheese. I generally require salt for most any dish the players make, but this is totally up to your discretion. Will it fit your world? Salt wasn’t always as ubiquitous and easily obtained as it is today, entire wars were fought for its amazing capabilities at preserving food and turning dishes from edible to enjoyable. In the recipe books later on, it will be included, but feel free to omit it from what your players need to cook tasty dishes.

Spoiling

And finally, a note about spoiling. I primarily deal with this question when a party creates a restaurant, and it will be addressed for ingredients in the Restaurants section. When it comes to individual dishes that your players create, use your own discretion. If they’re going to argue that the egg and mayonnaise sandwich they made a week ago in the desert is still wise to consume, let them realize why it's not.

Meals

Not all meals are created equal. A peanut butter sandwich and a slow cooked beef stew are both meals, but one takes a few minutes while the other requires many hours to complete. Furthermore, the peanut butter sandwich probably won’t fill you with the same warmth and satisfaction of that stew. Different meals take different amounts of time and give different bonuses, in addition to being worth different amounts.

Time

First off let’s look at how much time it takes to make a meal. We have two categories of meals, simple, and gourmet. A simple meal will take one short rest to make, and a gourmet meal will take a long rest. This is obviously a very broad window for many different dishes, so feel free to rule this on a case by case basis, but for most mechanical purposes this has seemed fair in my games.

Bonuses

So aside from flavor (no pun intended), why should your players go out of their way to make a nice hearty stew after a long day of adventuring as opposed to the much cheaper and more portable options of hard tack and leathery jerky they’ve probably subsisted on for years?

When it comes to bonuses, we can go with the basic bonus from a proficiency with Cook’s Tools as seen in Zanathar’s Guide which is an extra hit point per hit die spent during a short rest. If we want to go this route, gourmet meals will bump that up to 1d2 hit points per hit die.

I know a lot of this guide seems like me taking convention and throwing it on its head for the sake of doing so, but honestly, this rule works well. In fact I would allow some players without such a proficiency to do it as well, or at least allow them to work towards such a proficiency in the future with enough practice.

But if you do want a little more flair and unique effects for each dish, I have included optional bonuses for each dish and ingredient that is described in the Recipe Book section (coming soon!).

Price

Price

Finally, price. Generally, your players will be the only ones consuming the ingredients they procure, but what if they want to offer their culinary services to others? They could haggle and set a price themselves for every single dish, or I have created a basic formula for finding what a dish should go for.

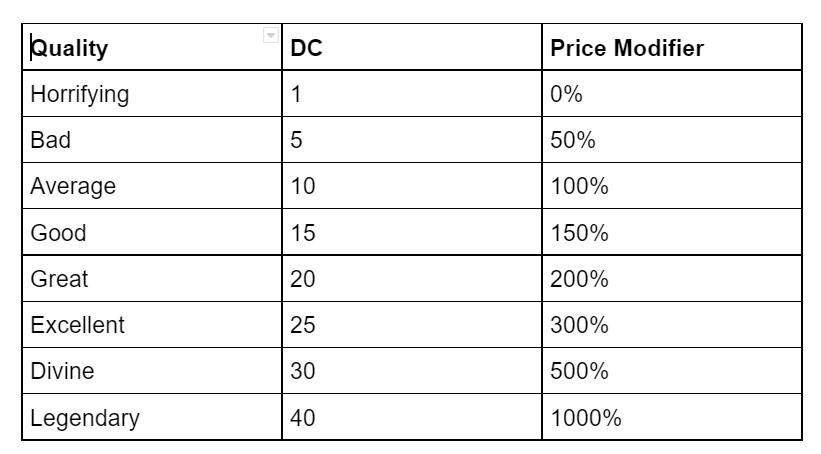

The base price of a dish is calculated at 1.5 times the total cost of the ingredients. This base price is then affected by the quality of the dish that the player creates. Remember that qualities are determined by their skill check, let’s expand the table from earlier.

This system will reflect the culinary skill of a player. Truly spectacular work should be rewarded, and throughout history we have seen people pay top dollar for food from the best chefs. The reverse is also true however, and if you take some good meat and serve wet slop, don’t expect to be making high returns. Also don’t think you need to use this table every single time a dish is made and sold. In the Restaurants section, there will be more discussion on pricing foods when selling to the masses, and some calculators to help do the heavy lifting.

Recipes

A collection of exactly how much of what ingredients go into a final dish. This guide contains recipes for a bunch of recipes that you can immediately include in your campaign. All of the items can be found in the Big Book of Items that is also included in this guide. Recipe layouts are simple, they will show the items, time, and optionally, tools that are required to make a specific dish.

One important decision when incorporating this overly involved style of cooking is how your party will use recipes. Will they be able to use any recipe that they have the materials for, or will the experimentation and acquisition of new recipes be a mechanic all on its own?

Furthermore what if these premade materials aren’t enough to sate your players. As exhaustive and general as I tried to make them, there’s no way I accounted for every combination of ingredients.

Creating New Recipes

This is where you can let your players make a recipe themselves. This can be done during downtime, or I guess a long rest. If they feel comfortable enough in a dungeon to start workshopping recipes, they’re braver than I am.

To do this, I split the skill check into three parts: ingredient preparation, cooking, and plating. Each of these gets a d20 roll, then you average the results and add the players cooking proficiency. Have the player tell you exactly what they are going to try to make and with what. If they pass a DC 15 skill check, they are happy with the new dish that they created and add it to their roster of known recipes.

For example, let’s say that my player Eldris wanted to make a new dish out of Owlbear meat covered in minced wild mushrooms, then wrapped with Fallbloom leaves and steamed. Assuming he had all those ingredients and the free time and equipment to make it, he will enter a new recipe skill check. He first rolls a 13 when prepping ingredients, next he rolls a 7 while cooking, and finally he rolls an 18 when plating. Averaging the 3 of these, we round to a 13. As he’s a level 5 character with 14 Wisdom and is proficient in the Cooking skill, we will add 5 to the final score (2 from his Wisdom Bonus and 3 from his proficiency modifier), giving an 18 for the skill check. The dish is a success to the chef and, while they know where they can improve it in the future, is good enough to add to their roster. I also like to give the first person to invent a new recipe a +2 bonus to cooking checks when making that recipe from that point on as a little reward for exploration. I then write that recipe down in my recipe book as “Eldris’ Steamed Owlbear” and forever more, it is one of his signature recipes.

The more involved cooking method listed above is also rather interesting when asking the party to make a more important dish; something that would require all of their attention and skill. Something like the birthday feast for a head of state or in an Iron Chef style cooking competition (have fun with that plot line, on the house).

Tools

It’s hard to make an omelet without a pan and a spatula. It's difficult to simmer a soup without some sort of vessel to hold its contents. For most simple meals, Cook’s Utensils will create something passable. Feel free to require this simple 1gold and 8lb item as your player’s gateway into the culinary arts. However let’s take a look at exactly what Cook’s Utensils are. As defined in Xanathar’s Guide to Everything on Page 80:

Adventuring is a hard life. With a cook along on the journey, your meals will be much better than the typical mix of hardtack and dried fruit.

Components. Cook's utensils include a metal pot, knives, forks, a stirring spoon, and a ladle.

While a nice stock pot and a spoon can get you most of the places you need to go with cooking, it would be rather difficult to make the aforementioned omelet. That isn’t even to speak of the attachment that some chefs have on their specific tools. And for good reason. Deboning meat, or chopping fresh produce is a completely different task depending on if you’re working with a honed blade or some dull hunk of metal. With all that being said, I am not particularly strict about this in my own games. I generally don’t ask if they have the proper paring knife when processing fish, or if they made sure to get the right size nozzle when doing some piping work. But it can be fun to include some interesting tools that will give your players some extra bonuses, should they decide to go out of their way for them, or invest in them. Not every single item needs to be magical in nature. Plenty of knives are just darn good knives, and their usefulness shows in the hand of the right chef, so feel free to give out some +1 knives, or +2 stock pots.

If you want some more wacky options though, here’s a list of some interesting equipment to allow your players to upgrade their cookery. More will be included in the Big Book of Items.

Honed Honing Steel

Value: 20 gold

Weight: 3lbs

This metal rod will keep your knives in tip top shape, and a sharp knife is a useful one. When harvesting meat from a carcass, you may sharpen your knives first to get 1d2 extra materials of that type.

Pressurized Pot

Value: 250 gold

Weight: 8 lbs

A soup pot inhabited by the spirit of a water elemental who pressurizes the liquid inside. This item allows you to make gourmet soups and stews in a short rest instead of a long rest.

Vorpal Knife

Value: 10,000 gold

Weight: 1 lb

This knife cuts like no other, allowing for the most fluid of slices through any culinary materials. There are rumours that one is used by the head Chef of the Royal Academy of Cuisine up North, but it's doubtful you’ve ever seen one in person. This knife gives a +3 bonus to Cooking skill checks when cutting ingredients.

Automatic Stirring Spoon

Value: 500 gold

Weight: 1 lb

This spoon has a mind of its own. And that mind is set on stirring any liquid it is put into at the perfect speed to keep the bottom from burning. This spoon gives a +1 bonus to Cooking skill checks when making soups and stews.

Pre-Seasoned Pan

Value: 1000 gold

Weight: 5 lbs

The Culinary Wizard Treyfus Stock created a collection of enchanted cooking vessels, and this is one of them. Anything that goes into this pan takes on a faint flavor of spice in a way that perfectly compliments the dish. Any modifier ingredient of Tier 1 or Tier 2 quality, can be treated as Tier 3 quality when cooked in this pan.

Running a Restaurant

So let’s say your players are just as passionate about food as I seem to be and making it for their party isn’t enough. How do they go about making it for the masses? Well Hilda the Half-Orc isn’t the only one who can open up a tavern. The DMG already has rules for running a business which you could definitely use. But this is an overly involved guide, so let’s dive into some more in depth ways you could set it up.

Costs and City Size

To start, all Costs mentioned moving forward are dependent on the city size that the restaurant is hosted in. Raw ingredients and labor will cost more in a big city than a small hamlet, but the same is also true of profits. While this does work out to be about equivalent in the long run, what it does mean is that a spell of bad luck can hurt a lot more in a big city if there aren’t reserves of capital in place to take the blow.

Village (Population Less than 1,000) : Base Cost

Town (Population 1,000 to 5,000) : Base Cost * 2

City (Population 5,000 to 25,000) : Base Cost * 3

Capital (Population Greater than 25,000) : Base Cost * 4

What does a restaurant look like in each of these different scales? In a Village, your restaurant will probably just be a small storefront with a few chairs, perfect for your neighbors and locals to come by for a quick meal after their day of working is done. That storefront might even be your own house, just retrofitted to seat a patron or two. You won’t need many employees at all, and many of these house-front stores are just places that sell the same things they have for dinner themselves. Don’t expect too many visitors from far off lands, while many of these village storefronts are true hidden gems, they are definitely very hidden.

Once you open a restaurant in a town, you are probably looking for more space, more employees, and more patrons. No longer will your front yard suffice, you’ll be visited by people all around town, and word travels fast, whether for good or for worse. It will be much more common to serve travelers who are just stopping through, and let’s hope you treat them well, as they will carry your praises back to the cities they came from. Assuming you are able to build up enough of a good reputation, you can expect some of the more culinarily invested to make some pilgrimages out to sample your restaurant.

If you open a restaurant in a city, you are now at the level of serving many more strangers than friends. You will be held to a much higher standard than in the small Towns, because your patrons can always just go down the road to somewhere else. Competition is fierce, and margins are razor thin, but customers in the cities carry a lot more coin than they do in the villages and towns. Expect good word to bring in new customers from all over the city, and many other towns and cities as well. On the other hand, a bad reputation will mean you will often get passed up for the other options.

Opening a restaurant in the Capital city is quite a difficult task. Competition is even fiercer than in the cities, and people around here are much pickier than those in the villages by virtue of more great options. Only the best of the best food survives here, and on top of that, just opening a place can be difficult. Securing land for a new restaurant can be difficult to do and won’t be close to the city center. Purchasing an old one to renovate can be even more costly simply due to location, but play that by ear and possibly give your players discounts or abilities to inherit it like in Dragon Heist. Of course all of that assumes that the local government is approving all your permits and requests. You can get away with selling food out of the front of your house in the villages, but here, the lords and ladies want a cut, so don’t forget to pay your taxes. But if you can weather the storm of establishment, and attract a consistent clientele, then you can expect patrons from the highest corners of society to pay you a visit. The best restaurants in the Capital are the kind that students in Culinary Schools in other countries learn about. Their chefs get contracted to prepare dinners for kings and queens. These chefs have just as much sway and diplomatic pull as some dignitaries. Getting there is difficult, nigh impossible, but so worth it.

Trimming the Fat

The next sections are going to get into a lot of numbers, tables, and spreadsheets. But what if you just want to have something simple to track exactly what happens with your players’ restaurant and how much money they make? In short, let’s break down the necessities: Restaurant Cost and Upkeep.

If your players aren’t inheriting it, I would price the base cost of a previously owned restaurant at 2000 gp (adjusted by the city size table above). If they wanted to build one, I would put the base cost of supplies and labor at 2500gp and 60 days' time, with cost once again adjusted by the city size table. I would refer to the Building a Stronghold section of the DMG on page 128. As far as Maintenance cost, I would put the base cost at 5gp per day.

As far as upkeep I would make some erratas to how upkeep is calculated in the DMG.

Rolls:

1 : Lose Maintenance * 2 per day

2-15 : Lose Maintenance * 1.5 per day

21-30 : Lose Maintenance per day

31 -40 : Lose Maintenance * .5 per day

41-50 : Break Even

51-70 : Gain Maintenance per day

71-90 : Gain Maintenance * 2 per day

91-99 : Gain Maintenance * 3 per day

100 : Gain Maintenance * 5 per day

I would also add a rule to allow putting off debt. Being out of the money for one bad night doesn’t make a restaurant shut down. However, being in the red does make it harder to function. So I would add a -5 cumulative penalty to rolls per night, until that debt is paid off.

Feel free to roll all of these per a week instead, just multiply the result by 7, but plenty of times my players love to throw those dice day after day and chart exactly how they are doing. I also have a calculator for this built, I will be posting it on my site soon.

As a DM, adding bonuses or penalties to these rolls would be a good way to reflect the environment of that business. Maybe there is a festival in town, or the royal family is traveling through for some ceremony. That will drum up business and give a bonus. Or what about goblins raiding the town or causing issues with your suppliers? Probably gonna get some negative penalties. These modifiers can also present themselves as adventure hooks. Maybe you really want to get your players to investigate a nearby bandit caravan interrupting that’s been harassing the locals but your party just doesn’t care, or think it doesn’t affect them. Try hurting their bottom line instead of appealing to their ethics and you’ll see them get a move on.

Putting it all together it would mean that for example, with a Restaurant in a Town (Base Cost * 2), a player rolls for how it did over the course of a week. They have a +10 from some marketing work they spent their downtime doing and some good roleplaying. They end up rolling a 58. After adding their bonus, they have a 68 total, so refer to the table. They would break even and then make back their Maintenance cost in profit. We adjust the Base Cost for the fact that they are running a restaurant in a Town, so they make 10 gold per day, or 70 gold that week.

I’ve run the numbers, and with this probability distribution, in the long term your players will make about 50% of the maintenance cost per day, which I feel is a fair amount. This would also mean that it would take them about 2 years to make back their investment on the restaurant. Feel free to tweak these numbers as always.

This method is also very much impacted by bonuses, well, as everything in D&D is. I highly recommend giving out temporary maintenance roll bonuses often as a good way to reward your players for active participation in taking care of their restaurant. Penalties can be just as useful, and can serve a good purpose to get your players moving to fix a problem. The following table gives some ideas of different maintenance roll bonuses and penalties to give your players based on their actions. The reasons are just examples, feel free to replace them with whatever comes up for your party.

Modifier

-10 : You messed up colossally, the king got food poisoning at your restaurant, or you have ran out of all good will in an area

-5 : You made a major faux pas, you served the Elvish Druid roasted Owl and you are the talk of the town for it

-3 : The rat problem is getting a little bit too obvious

-2 : A rival restaurant released a smear campaign against you, or a client found the Dwarven chef’s beard hair in their soup

-1 : You keep running into supply chain issues and customers are getting annoyed

+1 : You have consistently served your patrons well and some of them are recommending their friends

+2 : The new menu dish is a hit! People are flocking around to try it

+3 : You ran a successful marketing campaign such as a festival, and your name is all the buzz around town

+5 : A high ranking noble asked you to cater his wedding and he loved it.

+10 : You have returned from your quest with the legendary ingredient, and everyone who’s anyone is watching to see what you do with it.

These reasons are far from all of the ones you can use, they are just there as a set of examples for you to draw on, and to realize what magnitude of actions result in what kind of roll modifiers.

The tables above are really all you need to use to run a restaurant. A lot of DND is about abstracting away the nitty gritty, even more so in 5e, and there is nothing wrong with that. The maintenance table and the roll modifiers you grant your party can be a representation of everything going on at the restaurant. Then simply use its results to determine when things are going well and when they aren’t.

But if you do want to get more in depth, the following sections will be going into additional mechanics I have developed for restaurants. Feel free to use them all, none of them, or to pick and choose which ones seem interesting or fit your DM style.

If you made it to the end, thanks! Let me know if you have any feedback. This is still pretty rough as I’m working on formatting and sections on Restaurants, World Building, and then the two accompanying books “The Big Book of Recipes” and “The Big Book of Items”, but they should be ready in the next few months. Hope this is helpful to your own campaigns. Get cookin!